In February, 1967, I got a magazine to send me to San Francisco. I was working at Crawdaddy! magazine, and living in the office in Greenwich Village, and the editor, Paul Williams, couldn't stop talking about the music he'd heard when he'd gone there the previous fall. I couldn't wait to see it all, so much so that I didn't bother to think the trip out, and as I was leaving the office on my way to the airport, the guy in the apartment next door appeared. We didn't know him, just knew that he had really long hair and his name was Chan. He asked me where I was going, and when I told him, he asked me if I had a place to stay. I didn't. "Okay," he said, and wrote an address on a piece of paper. "These are friends of mine. When you get there, ask for Luria. I'll call them and tell them to expect you."

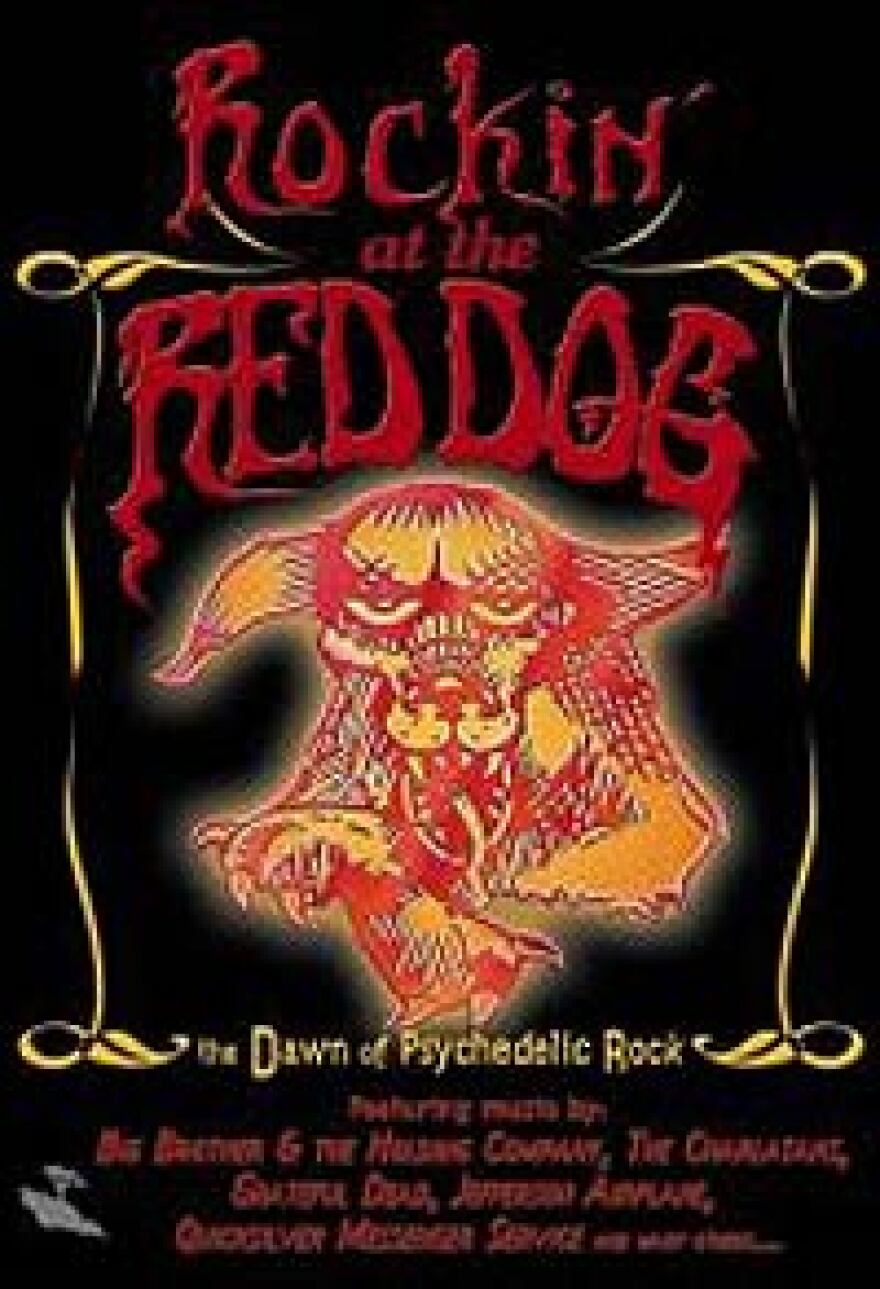

In retrospect, the introduction Chandler Loughlin gave me to Luria Castell, Ellen Harmon, Lynn Hughes, and Alton Kelley at the beautiful old Victorian house I arrived at some hours later plunked me down in the middle of a piece of American cultural history that Mary Works has resurrected in a remarkable film about the bar these people and their friends, who also included her parents, ran in Virginia City, Nevada starting in the summer of 1965.

The Red Dog came into being when Mark Unobsky's father warned his ne'er-do-well son that he'd better find something to do with his life, whereupon Unobsky talked his dad into buying a building in downtown Virginia City that he could get his friends to turn into a retreat from their lives as students and workers in San Francisco. A number of them, including Don Works, a former house-painter, had already moved to Nevada , and he talked others, most notably Chandler Loughlin, who'd run folk-music coffee-houses, into joining the team. The idea was to open a bar with live music and great food so they could all make money and continue to live the way they wanted to, which included smoking a lot of pot and having fun.

Loughlin recruited a chef, Jenna Worden, a mistress of ceremonies, Seattle folksinger Lynne Hughes, a dishwasher, former political radical Luria Castell, and a gigantic bouncer, a Washoe Indian named Mike Jones, and then found the band that would provide the entertainment, a well-dressed quintet from San Francisco who called themselves the Charlatans. The Red Dog Saloon, as it was called, opened in June, 1965.

The Charlatans played mostly electrified folk music, a trend just getting underway, most notably with the Byrds in Los Angeles. All of them were inspired by Bob Dylan, who had spent that spring touring England saying good-bye to his protest-singing folkie past, a tour captured by filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker in a film which was released in 1968 under the title Don't Look Back, and which has just come out on DVD with an entire extra hour's worth of outtakes Pennebaker has entitled Bob Dylan 1965 Revisited. At the time of the tour, Dylan had already recorded an album, half electric and half acoustic, called Bringing It All Back Home, and had released a rock and roll single called "Subterranean Homesick Blues" which pointed his work in a whole new direction. In a famous scene from the film, Dylan, with Allen Ginsberg lurking in the background dressed as a rabbi, stands tossing cards with key words from the song as it plays on the soundtrack, an early music video.

When the Red Dog's first summer was over, the Charlatans returned to San Francisco, as did Alton Kelley, Luria Castell, and Ellen Harmon. Inspired by what they'd just been through, in October they formed a company called the Family Dog, and on October 15, they rented Longshoreman's Hall and put on a dance with music by the Charlatans, Jefferson Airplane, and a band that lived a couple of doors away from the Charlatans, the Grateful Dead. The San Francisco Chronicle's jazz critic, Ralph J. Gleason, covered the event and noticed that the dancing went on non-stop, as if people's lives depended on it.

Gleason was astonished, but he was also savvy enough to know that something was happening in his city as folkies began going electric and writing their own material. In December, Bob Dylan and his new band showed up to play some dates in northern California, and Gleason, who had a program, Jazz Casual, on the local noncommercial television station KQED, invited Dylan to a press conference, which was taped and broadcast – and, now, released on DVD. Salting the audience with friends of Dylan's like Allen Ginsberg and interested parties like the business manager of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, Bill Graham, Gleason refereed nearly an hour's worth of inspired repartee from the 24-year-old songwriter. Graham, no fool, had presented Dylan with a poster for a show he was promoting on behalf of the Mime Troupe, featuring a number of local bands. Dylan read off the names and said with a grin that he'd be busy that night but otherwise he'd like to be there.

Graham's poster was very standard: pictures of the bands laid out in a grid. But Alton Kelley of the Family Dog was a trained artist, and soon the Dog's weekly dances were announced with posters that became increasingly sophisticated. By the time the Red Dog opened again in 1966, this time with Big Brother and the Holding Company, who hadn't yet met Janis Joplin, in residence, the San Francisco scene had already been born, and the sense of community, the innocence, and the feeling of creating a new society, were already a year old. By the time the media's "Summer of Love" came along, they were already in retreat. But, as Luria Castell says at the end of Rockin' At the Red Dog, they never really disappeared.

I for one hope she's right.

Copyright 2022 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.