The Spokane Police ombuds' office serves as a check and balance over the department charged with keeping the community safe.

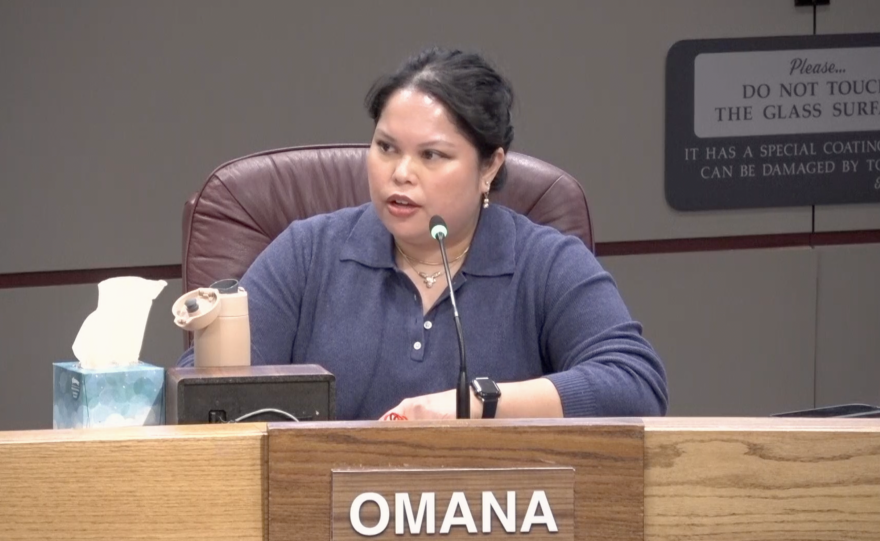

"I certify cases, attend IA (internal affairs) interviews, I attend review boards, and the ones I primarily go to are use of force and collision and pursuit. And then he goes to administrative review boards and deadly force review boards. But in his absence, I go to those as well," said Luvimae Omana, the second-in-command in the ombuds office to Bart Logue.

There has been debate about how much authority the ombuds should have.

"We don't have anything to do with discipline. But I think that the real tool in this job is persuasion and influence, because we all want the same thing. We want better policing services for the community. We want officers to be safe. We want the community to be able to, like what's happening here in Spokane right now, protest peacefully. And then everybody can go home at the end of the day."

Omana is leaving her post this summer. SPR's Eliza Billingham talks with her about the office and her job.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

LUVIMAE OMANA: I was an eager, soon-to-be law school grad, and I had heard that if you pester the Career Center, you'll be at the forefront when they have job openings. So I was there every single day. So then this opportunity came up through the city where they needed a person, any person, to work in the police ombuds office.

It was strange how quick it went. As someone who really wanted a job, I was of course excited, but also a little bit skeptical at the pace. And so I met with the then city attorney. She made it clear that I wasn't going to be there for the ombuds function, but as like a complaint intake coordinator. And so this was 2015. This was the time when Rachel Dolezal was making national news about her activities outside of the commission.

ELIZA BILLINGHAM: Just a little refresher, Rachel Dolezal was a white woman in Spokane who claimed to be Black. She was the head of the NAACP from 2014 to 2015 until the truth about her race came out. She was also accused of workplace harassment during her time on the Office of Police Ombuds Commission.

LO: So I've done everything from be that front window person to when they eventually hired an ombuds because I was there before the ombuds. He wanted to keep me on. He saw the value of what I could bring to the office.

Bart is a really big picture person and was like, I see you as being my deputy someday. And I was just like, chill out, dude. I'm going to be here for a year maximum.

I'm not even from the state. I just wanted to work a little bit before I move back home, get some work experience. And he's like, we'll see.

EB: And what were your responsibilities once you became deputy ombuds?

LO: Yeah, so the deputy has the same responsibilities as the ombuds. We set it up that way because we're such a small office. It's primarily the two of us doing the oversight function.

Really, I certify cases, attend IA interviews, I attend review boards, and the ones I primarily go to are use of force and collision and pursuit. And then he goes to administrative review boards and deadly force review boards. But in his absence, I go to those as well. And then, yeah, we do report writing, which is a big part of our public facing work.

EB: Have you noticed any chronic issues with the SPD over your time as deputy?

LO: I want to start with this department. It's overall a good department. We don't see the issues here that you see like in the East Coast, where there's police officers who are actual like doing criminal type work. So that I've not seen here. But I think an issue that is present here, but also in all of policing is the culture of policing.

After George Floyd, I think there has been like a morale issue with officers, then there's kind of been like a closing of ranks and this us versus them. So kind of rebuilding that trust with community, but also within the department. You know, something that I know Chief Hall is really like, is an emphasis for him is supervisor responsibility.

All of these people at some point, perhaps were peers. So then when someone gets promoted, and now they are your supervisor, sometimes it's harder to be like, hey, this is what you should have been doing. I think there's this fear a little bit of if you give feedback, it's, hey, you weren't there, you didn't live this experience.

Or I already like know that it was wrong. Why are you beating a dead horse? Like I've been in conversations where this is the response. And so I think turning that perspective to be more, this is critical feedback, yes, but it's to help you grow and develop so that this doesn't happen again.

EB: Do you have any guidance for how the public should think about police in a time where there seems to be a pendulum swing between either villainizing or glorifying them?

LO: I was a freshman in high school when 9-11 happened. And I just remember after that event, how much love there was for first responders. So that kind of stuck with me for a long time.

And it wasn't really until, you know, 2015. I believe that's when Michael Brown happened. And cases since then that escalated towards George Floyd, where I really saw this change in our society, the attitude towards police.

I am a person who doesn't like extremes in the first place. Like if I'm feeling too enthusiastic about something, I'm like, oh, you gotta take a step back. And if I'm feeling too negative, I'm like, well, I'm not usually this kind of a person. So why do I feel that way? You know, so I'm always trying to regulate. But as far as guidance to the community, I think a lot of the times when we think of officers, we think of these people in a uniform, and they kind of become one entity, kind of anonymous people. And so their humanity is not the first or second thing even maybe you think about.

But behind every uniform, I know that there's a person who got into this profession because they wanted to serve their community. They had the skills to do this type of job, which is very difficult because nobody calls the police for a good time. I think recognizing that is important, and that they want to have a career. They want to be able to go home to their families. And I think they get a disproportionate amount of attention for sure at this point in our history. But I think also attention can be turned into a good thing.

EB: What kind of power does the police ombuds office actually have?

LO: Yeah, so a lot of people who think they have an idea of oversight, and then they find out what we actually do. They're like, so you do nothing. You have no teeth. You can't enforce anything, even recommendations. Like you can't make them accept it. A lot of complainants are like, I want them fired.

We let them speak, get their frustrations out. And then at the end of every conversation, we let them know what we can do for them. And it's make sure that their concerns are adequately reviewed. And then if there are concerns to be followed up with it, they're properly reviewed.

We don't have anything to do with discipline. But I think that the real tool in this job is persuasion and influence, because we all want the same thing. We want better policing services for the community. We want officers to be safe. We want the community to be able to, like what's happening here in Spokane right now, protest peacefully. And then everybody can go home at the end of the day, you know. So how do we do that? And I think that's where the differences start to come up. But if we know that that's the same goal, we can at least have dialogue and compromise on how to get there. And then the formalized step of that is making the recommendation.

EB: And why are you leaving now?

LO: Part of it is I just had to set a date. I'm an only child and my parents are getting older. But also I think this job has a lot of challenges. It challenges me personally. Like I feel my watch be like, your heart rate's going up when I know I have to have like a hard conversation with someone.

One of the things I really enjoy about this job is the only requirement is to stand up for what you think is right. So even if everyone else in the room disagrees, which happens when I'm in a room full of police officers, I came to this conclusion because that's what I think is true and how we fix it can be discussed. But I have to say something. That's what's kept me here for a long time.

EB: I’ve been debating asking you this question, but you took this position when you were a young woman of color, which you still are and you're even like smaller in stature than most police officers. Does that affect your work?

LO: To add to that, like my background is different for most of these officers and I'm oftentimes the only non-police person in a room.

I've been told that I have this thing called resting bitch face, which is quite intimidating apparently. So that I think works to my advantage a little bit. And I am a kind of person that tends to listen more before I speak.

And apparently that helps with the intimidation factor. I'm thankful that I have this seat in the room. Sometimes I'm like, how did I get here? But I always go back to the requirement is to do the thing that you think is right. Everyone's been respectful enough at least to let me be heard at the table.

EB: Where does this conviction to stick up for what you think is right come from?

LO: I don't know. It's something I think about all the time because no one else is going to know. The public's not going to know if I don't say anything. My boss isn't going to know. It's really just what am I okay with? I wouldn't like the person I was if I didn't say what I thought was right in those moments where no one else would say anything.”