Updated at 3:40 p.m. ET

A new analysis of data from Fukushima suggests children exposed to the March 2011 nuclear accident may be developing thyroid cancer at an elevated rate.

But independent experts say that the study, published in the journal Epidemiology, has numerous shortcomings and does not prove a link between the accident and cancer.

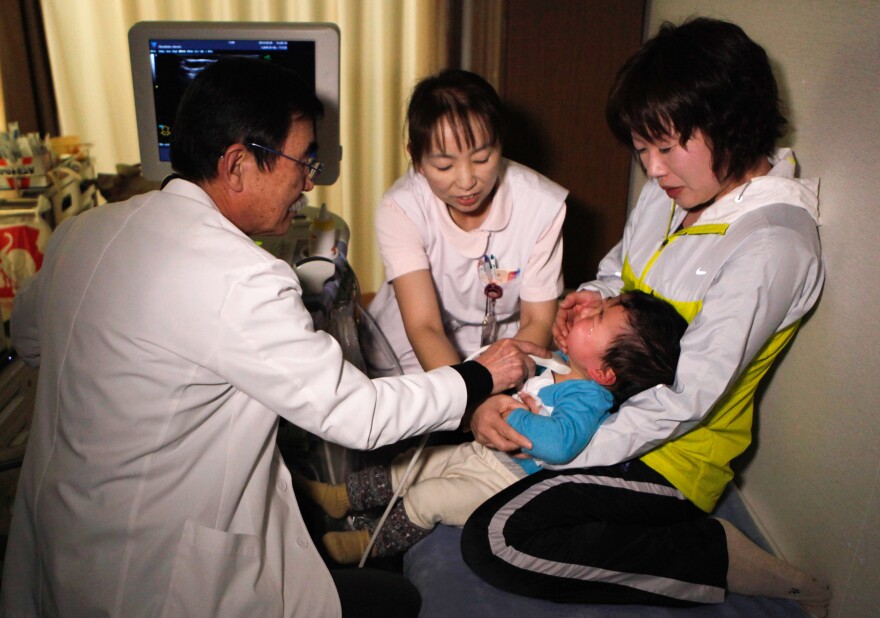

The work, led by Toshihide Tsuda of Okayama University, is based on a large public health survey that was set up in Japan's Fukushima prefecture following the accident. As part of the survey, children who were living near the plant at the time of the accident have been offered regular thyroid screenings.

Thyroid cancer can be caused by radioactive iodine released in a nuclear accident. Children are particularly susceptible because their thyroids are growing rapidly. Thyroid cancer was listed as a possible health risk in a World Health Organization report on Fukushima, though the report stated it would be difficult to link cancer cases to the accident.

In the past year or so, the Fukushima Health Survey of more than 150,000 children has turned up 25 "suspicious or malignant cases" of thyroid cancer. Thyroid screenings in previous years have also found numerous cases.

Japanese officials believe the screening process itself may be behind the numbers. Increased vigilance might be turning up thyroid abnormalities that otherwise would have gone undetected.

But the new paper contradicts that view. The increase in cancer is "unlikely to be caused by a screening surge," the paper says. It says thyroid cancer rates are highly elevated throughout Fukushima.

Other researchers are skeptical of the new result. Geraldine Thomas, a professor at Imperial College who has studied thyroid cancer from Chernobyl, says the analysis incorrectly compares the screening in Fukushima to clinical cases of thyroid cancer in which patients are already sick. The comparison falsely suggests thyroid cancer in Fukushima is elevated by as much as 50 times compared with the general population. "This is not a very good paper to be basing opinions on," she says.

More accurate comparisons between residents within different parts of Fukushima prefecture show no statistically significant variations in cancer rates, she says.

David Brenner, director of the Center for Radiological Research at Columbia University, adds that the study makes no effort to trace the exposure of patients. "It's simply relating geographic regions to cancer risks and not looking at individual radiation doses," he says, adding that without that information, it's virtually impossible to connect the screenings to the accident.

"It really doesn't tell us the whole story," he says.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.