The story about contaminated groundwater beneath Spokane’s West Plains is well known. For years, firefighters at Fairchild and Spokane International Airport used fire suppression foam containing chemicals known as PFAS. Those chemicals are believed to be harmful to human health. In 2017, Fairchild discovered foam had made its way into the groundwater and spread beyond the boundaries of the base. Contamination was also discovered at the airport. PFAS was detected in the wells of nearby homes and businesses.

Scientists, such as Eastern Washington University geology professor Chad Pritchard, are tracking the whereabouts of PFAS and where it’s migrating. Pritchard's PFAS work is co-mingled with other research he began around the time the contamination was discovered. He was looking for the answer to the question: how much water lies beneath the West Plains?

This interview was lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Chad Pritchard: Airway Heights a couple years ago lost their water right to the Park West well because they drew down that aquifer like 400 feet, and so people that had wells, who have had production wells for their houses, could no longer get water because the water table is down below their well. And these wells are expensive to drill. So they lost that water right. So there is a water concern about water quantity as well.

If you go to like Saudi Arabia, they actually treat their wastewater to a very high level, like Airway Heights does, and a lot of places do, and they inject it back in the aquifer. If groundwater is flowing a foot a year, they'll go down like 20 feet or 100 feet and they'll pull it back out again. So it's treated, but then it also goes to the soil, and that treats it more. There's bacteria down there that can treat it, and it can pull that water back up, chlorinate it, and then it's drinking water. It's called aquifer storage and recovery. So we pump it down the storage, recover it back.

Right before I started teaching here, I worked for Budinger and Associates, and we drilled some of those wells, test wells for it, and so I was kind of enamored by this topic. Then we read about PFAS, and I was like, whoa, I can't be telling people to pump water and then pull it back out if the soil is contaminated with PFAS. And so it kind of just turned from groundwater to where is this PFAS even going? And without this study, I don't know that we would know any of that.

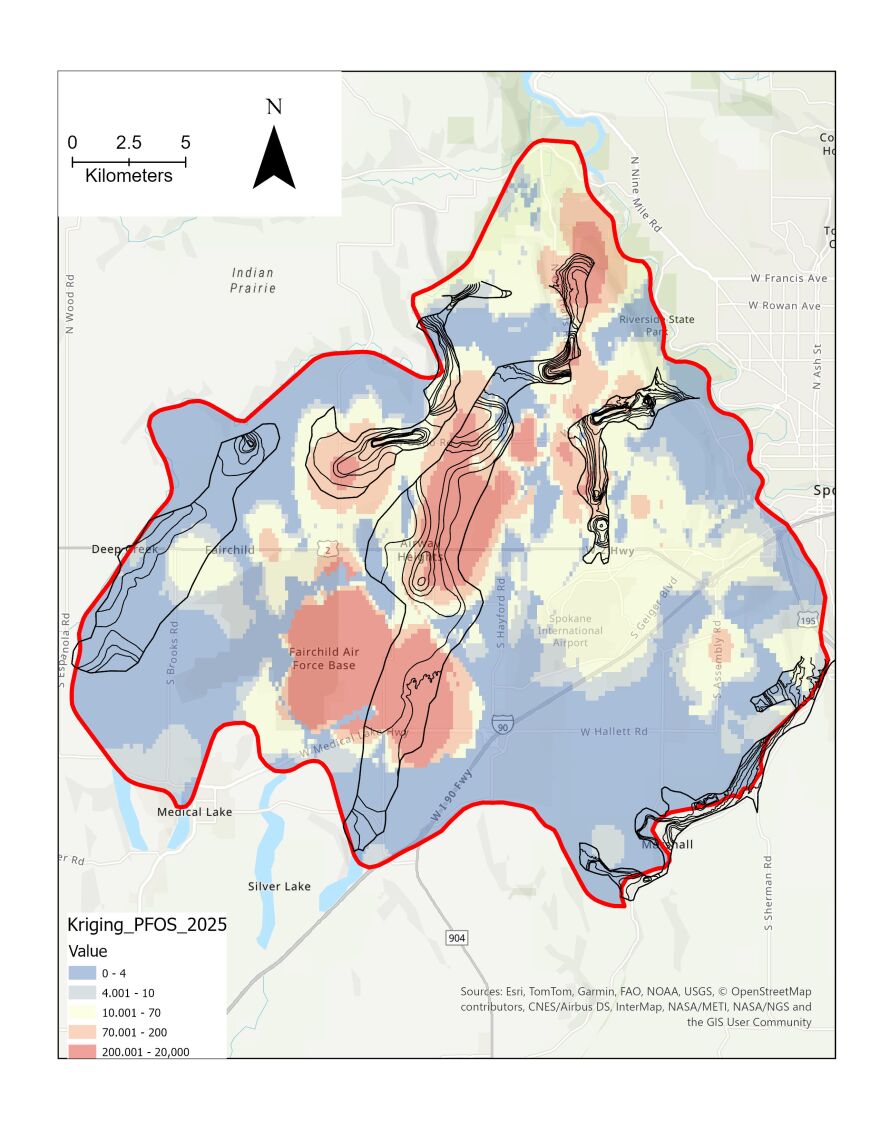

Now we've actually gone out and sampled like over 200 wells over two summers and then combined all of everybody's data, which nobody else wanted to do. They're just like, these are my data. EPA's got this north of the Spokane International Airport. Fairchild does Fairchild. We're able to pick up the whole West Plains and put it all together.

DN: How many more are out there to be sampled?

CP: We put a little map together where we took at least our database for the paleo channel paper. So we went, combed the water resources or the Department of Ecology water well report.

We have this map right here that kind of shows you the wells that we know of. There's more than that. It's probably only like a half of the wells maybe. Maybe two-thirds that we know about. And then we've only sampled like that many, essentially. So there's still another 1,000, 2,000 people out there.

DN: What more would you learn by being able to talk to those people? Or do you feel like you've got enough information right now that you've got a pretty good feel for?

CP: I'm stoked about how much data we have. But you know us scientists, we could always use more data.

DN: Pritchard and his students have developed a 3-D model of the geology of the West Plains, where the water is and where it’s going and they have a good idea where the PFAS has settled.

On the question of water supply, he says the next step is to create an aquifer protection district. People in the West Plains cities will be asked next August to authorize a small tax to fund the district, which is similar to what Spokane has had for decades. The money raised will be used to protect the quality of the groundwater on the West Plains.

CP: It'll go all the way down to Cheney, because Cheney has their own issues, They had to close down Cheney Water Well 5 because of higher PFAS levels. At the time, it wasn't above standards, because the standard in 2017 was 70 parts per trillion. But then in 2022, it went down for state action levels, down to about 10 to 12. And then in 2024, the levels actually went down to 4 parts per trillion for municipal, like public wells. So they closed down too. So they have kind of a PFAS issue as well, which is a new study that we're starting to get into now.

DN: Pritchard says his research should be helpful to Spokane County’s new PFAS Response Task Force, which was formed as an advisory body to provide information to the government agencies and others that will make decisions about how to help people with contaminated wells and supply them with clean water.

The task force is chaired by County Commissioner Al French and Spokane Regional Health District Health Officer Dr. Frank Velasquez. Other members include Medical Lake Mayor Terri Cooper and Airway Heights City Manager Albert Tripp, as well as members of several citizen groups.

Pritchard is also exploring the question: Can the West Plains water supply support a population that’s much greater than what’s there now?

Over the last quarter century, studies have been done to investigate a variety of water-related issues, such as why so much of the area floods during the spring. Researchers have studied underground rock formations and channels where water moves and how old that water is.

CP: If you went back to 2010, the groundwater age and the groundwater, groundwater on aquifer, like the lower aquifer, was probably 12,000 years old. This last summer we went out and it was like 4,000. So that age is decreasing. There's a potential that has something to do with the fact that we were sampling people's residential wells as opposed to monitoring wells.

So if we're pumping all this old water out, we're taking all the storage that we had and reducing it. So maybe the groundwater levels aren't going down yet, but once you take that storage out and you have a couple bad years of rain, that's when the groundwater will start going down. And we have so many people in the West Plains depending on their own private wells.

And that's what's kind of unique about West Plains. We have two international airports that tested with PFAS and then downgradient are thousands of people that have private wells. Usually if you go to a town where there's an airport, it's municipal, so they have municipal water. They can drill a new well or they can filter it, but they can deal with it fairly quickly.

Here you can't blast water lines through basalt in any quick amount of time, and I don't know if you want to spend that much time and money to do that. So it's a very unique situation in the West Plains.

DN: I’m trying to understand, the age of the water is just the fact that it's there and it's available to draw upon?

CP: Yeah. If you already have like storage in your bank, in your savings account, you can always bring in water and you know if there's extra, it can flow like a spring. If we don't have that storage, if we don't have that old water and we don't get rain, then that water is going to start decreasing over time and time. And we're already starting to see that in springs from these older hills.

There used to be whole full rivers going through that maybe 50 years ago and that water no longer flows. If you go to the Petro gas station, there's the Ponderosa Pines RV resort. You can go in there and they have pictures of people fishing in that stream coming off that hill. There's no way there's water coming back. We've developed it so water can't infiltrate as easy. It runs off a lot faster. And then we're just pumping that water out.

DN: So you essentially bleed the place dry if you brought too many people in with too much demand for that water.

CP: If you keep on, yeah, if you keep on putting wells, you're going to drink up the whole milkshake, so to speak. Because when we do suck out water, we kind of have this calmer depression like you do when you suck a milkshake.

And people are like, we can keep on bringing water from the Spokane (River). That is one fix that will probably happen for Airway Heights is to pull water from near where Fairchild pulls water, and then they can have water.

DN: If you've already got issues with the volume of water in Spokane River, what do you gain by pulling water from the Spokane River up there?

CP: They're pulling water from the groundwater. I'm not going to say like, oh, pull it out all the time, but the groundwater levels actually are fairly constant in the Spokane Valley Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer. The flows, they vary from year. If you don't have a lot of snow, you're not gonna get a lot of flow. But those are really regulated by the dams, right?

If you look at older pictures of the Spokane Valley, people used to ride horses across the river, like in the summer, because the dams weren't releasing it slowly through. So these zones where the river is like losing, yeah, if the groundwater goes down at all, it'll lose a lot more regularly. But I think they've always gone dry.

DN: So this is more than just PFAS, this is an incredibly complex question regarding water supply, how it's used, that sort of thing.

CP: Oh yeah, it's a mess too, because we're like right next to Idaho, right? And so Idaho is kind of the state of Washington. The tribes are in there too. You have the Hutterites in our area that have a very old water right as well. It gets really complicated and the more we develop, I can understand that people want to develop, that's how you bring in taxes or whatever. But this is a pretty arid area. And if we're gonna start depending only on rain to recharge our aquifers, there's gonna be an issue.